The Plot Twisters community building journey is an on-going process. This document is maintained by Jenny Liu Zhang and Cat Chang and advised by Isaac Gilles.

A bulk of the writing emerged during Plot Twisters' residency in the Excavations: Governance Archaeology for the Future of the Internet cohort, hosted by the Media Enterprise Design Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder and King’s College London from July to November 2021.

A discussion of the Plot Twisters community model was exhibited at the United Nations Internet Governance Forum on December 6–10, 2021.

Moving away from implicit feudalism

When members of an online community encounter conflict, the default response is to exit due to the absence of basic democratic conditions (Schneider, 2020). Many platforms lack collective institutional tools to emerge change and transformation from within the community. Power is often incidentally distributed in a feudal hierarchy, in which one individual or a small group—often deemed moderators—establish, modify, and enforce values for the whole community. This minority is judge, jury, and executioner in situations of accountability (Schoenebeck & Blackwell, 2021).

Designing against implicit feudalism means intentionally creating conditions for members to advocate for their needs and organize to mutually fulfill them. One lens to explore the ever-evolving endeavor of self-governance is what Paulo Freire (1970) describes as “dialogue,” or the process of co-creating reality. Freire explains that “the starting point for organizing the program of education or political action must be the present, existential, concrete situation, reflecting the aspirations of the people.” Plot Twisters argues that the lived experience of a community member, including their emotions, needs, and motivations, are valuable mechanisms for creating contracts and accountability processes.

Plot Twisters comprises 20+ researchers, designers, and technologists passionate about the power of technology to facilitate self-reflection and emotional literacy. Over the last two years, we have been creating an eponymous digital game world of playful self-awareness activities and wellbeing resources. Out of our co-creation process, a novel approach to fostering participatory governance emerged: we use the very self-reflection practices we invent to communicate and negotiate values with each other. To finally document the journey of our community so far, Jenny and Cat participated as residents of the Governance Archaeology cohort in the Media Enterprise Design Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Freedom, play, and mutual aid

Plot Twisters began organizing in early 2020 on Slack, sharing thoughts and resources relevant to self-reflection across a handful of themed channels. Early discussions centered on the devaluation of wellbeing across existing educational and labor institutions, as most members recognized school as the first power structure that diminished their ability to make self-motivated decisions. As such, the first explicit value in the community was the freedom of all members to pursue their own interests at their own pace, in their own style.

Play, which was antithetical to experiences of traditional schooling, also became a guiding principle that helped us channel our intrinsic motivations. As low-stakes conversations in Slack evolved into robust creative collaborations with weekly meetings, members sought a way to communicate desires and plans. Defined as willful action motivated by the indulgence of curiosity (Schell, 2008), the value of play fostered conversations about consent. We used frameworks such as "yes, and" (Walsh et al., 2013) as a method to build upon each others' ideas, and this allowed each other to encourage trust, consensual creativity, and recognition of harm when it happens (Kaba et al., 2020). We were also inspired by the idea of “combinatorial play” in the process of creation, which emphasizes the permutations of possibilities that can emerge from exploring others' contexts (Calvino, 1987).

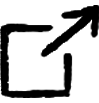

Jenny created visualizations to show the web of relationships she kept tabs on and managed in her mind. This first graphic shows how activities are distributed across active members. Facilitators of an activity are marked with soccer balls. Numbers indicate number of activities that person is responsible for.

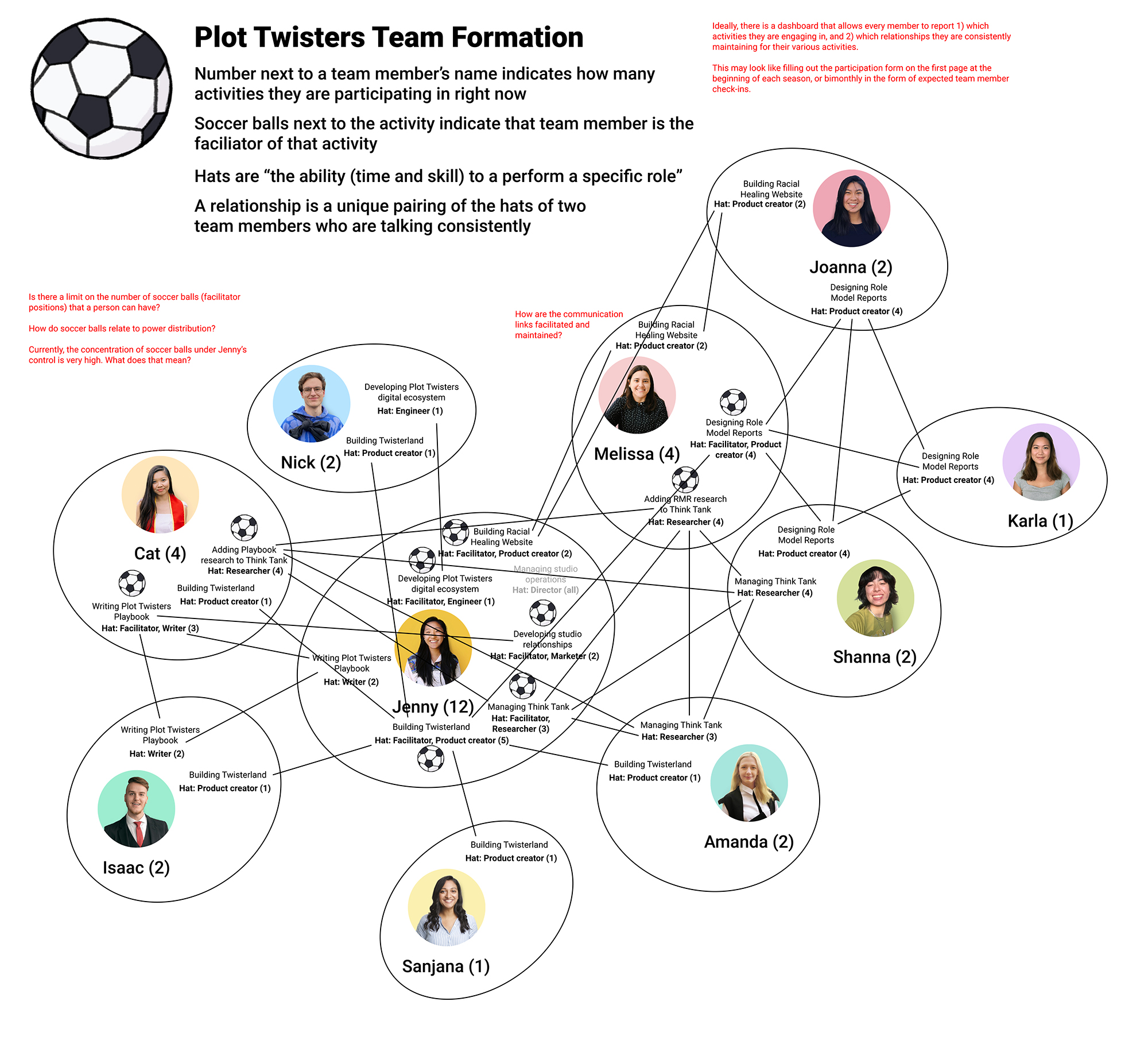

Jenny created visualizations to show the web of relationships she kept tabs on and managed in her mind. This first graphic shows how activities are distributed across active members. Facilitators of an activity are marked with soccer balls. Numbers indicate number of activities that person is responsible for. This second graphic breaks down the data of activity distribution and relationships into a table. People are labeled with a notation that indicates (1) the roles they play, and (2) the number of people they are working with.

This second graphic breaks down the data of activity distribution and relationships into a table. People are labeled with a notation that indicates (1) the roles they play, and (2) the number of people they are working with.As team projects formed and grew, members started a ritual of checking in on each others' feelings. The research of Antonio Damasio in Neurobiology of Human Values (2005) demonstrates that, no matter the individual’s cognitive ability, values emerge from the emotional and cognitive responses we have to social situations. As such, intimacy about our feelings became beneficial for a team’s ability to consensually play. Our practices look like what fellow cohort member Amelia Winger-Bearskin names “decentralized storytelling” (2021), or navigating one’s human experience in peer-to-peer story-spaces.

Building on our collective trust, we developed a practice of mutual aid. The mutual aid mindset involves harnessing the strengths of individuals in a collective; building a sense of “we-ness;” and using one’s own experiences for communal meaning making (Steinberg, 2004). In action, Dean Spade (2020) describes mutual aid as a form of participation where people care for one another while investing in the group. For Plot Twisters, valuing mutual aid allowed us to not only offer support to each other through psychological safety but also through resources, money, and emotional labor. This level of interaction helped foster bond based attachments which nurture stronger communities (Alberti, 2019), setting a precedent for self-organization of team strengths and self-determination toward solidarity.

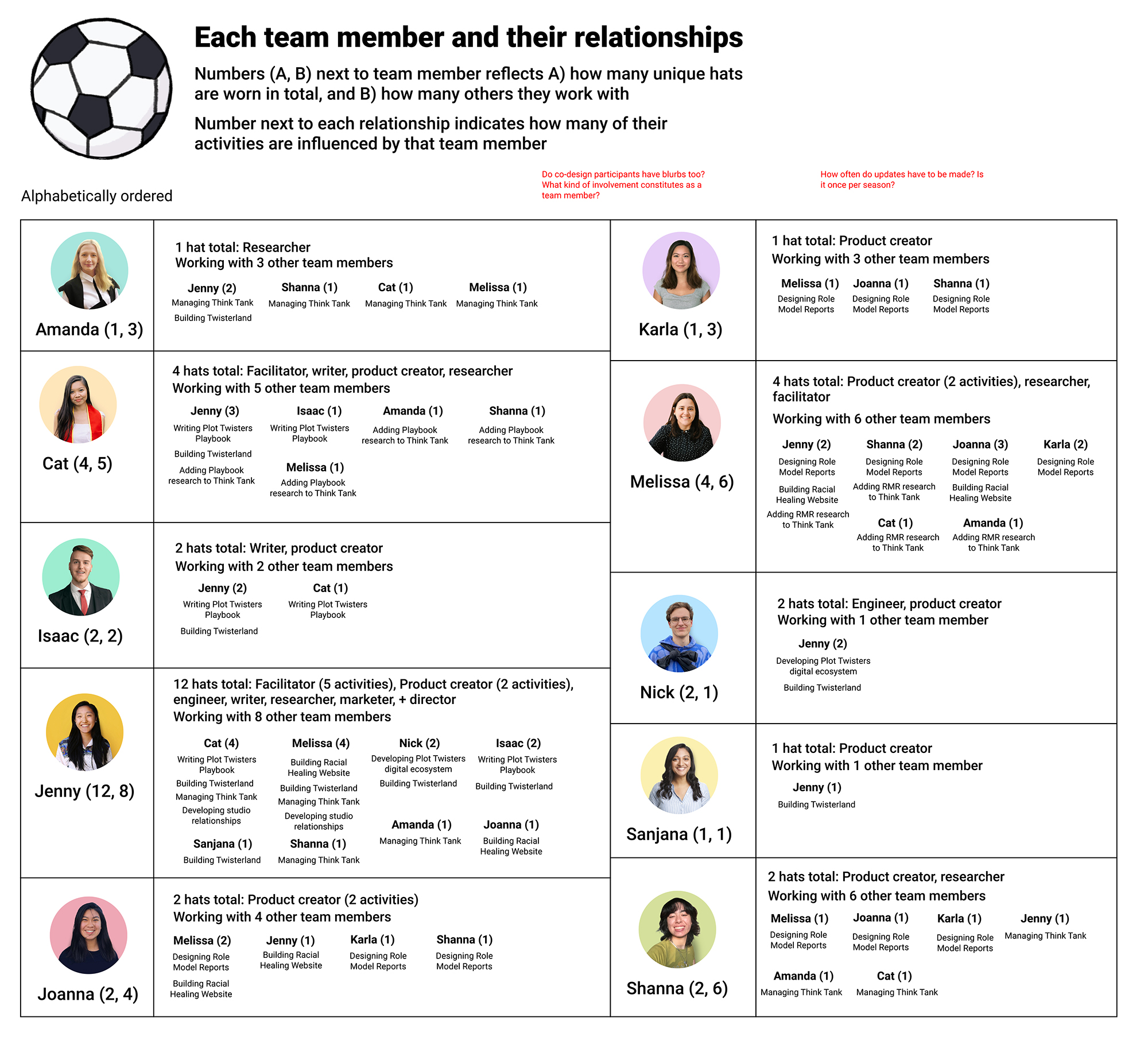

Cat visualized her idea of the community model as diverse and nested circles. While Jenny focused on describing the network within the team, Cat incorporated relationships to groups outside of the immediate core team.

Cat visualized her idea of the community model as diverse and nested circles. While Jenny focused on describing the network within the team, Cat incorporated relationships to groups outside of the immediate core team.Living in Twisterland as we build it

Plot Twisters was a centralized community by default because freedom, play, and mutual aid elevated the power of members who had the most time and resources to offer. This structure essentially resulted in an implicit “do-ocracy,” where select members had the most ability to “do.” The flaw with do-ocracies is that they may “fail to recognize that not everyone is equally equipped with the free time and other resources to participate” (Schneider, 2020). Members were interested in formally institutionalizing our overarching values, if not to distribute the authority, then to make the current distribution explicit and cohesive with how we saw ourselves: an organization antithetical to “relations of domination” (Freire, 1970).

As we explored our options, we documented the details that we did notice about our structure. Though we fell into centralization by default, we also always promoted voluntary participation, so boundaries and expectations around who could constitute as a member were nebulous. Jenny playfully compared these hazy borders to a shoreline:

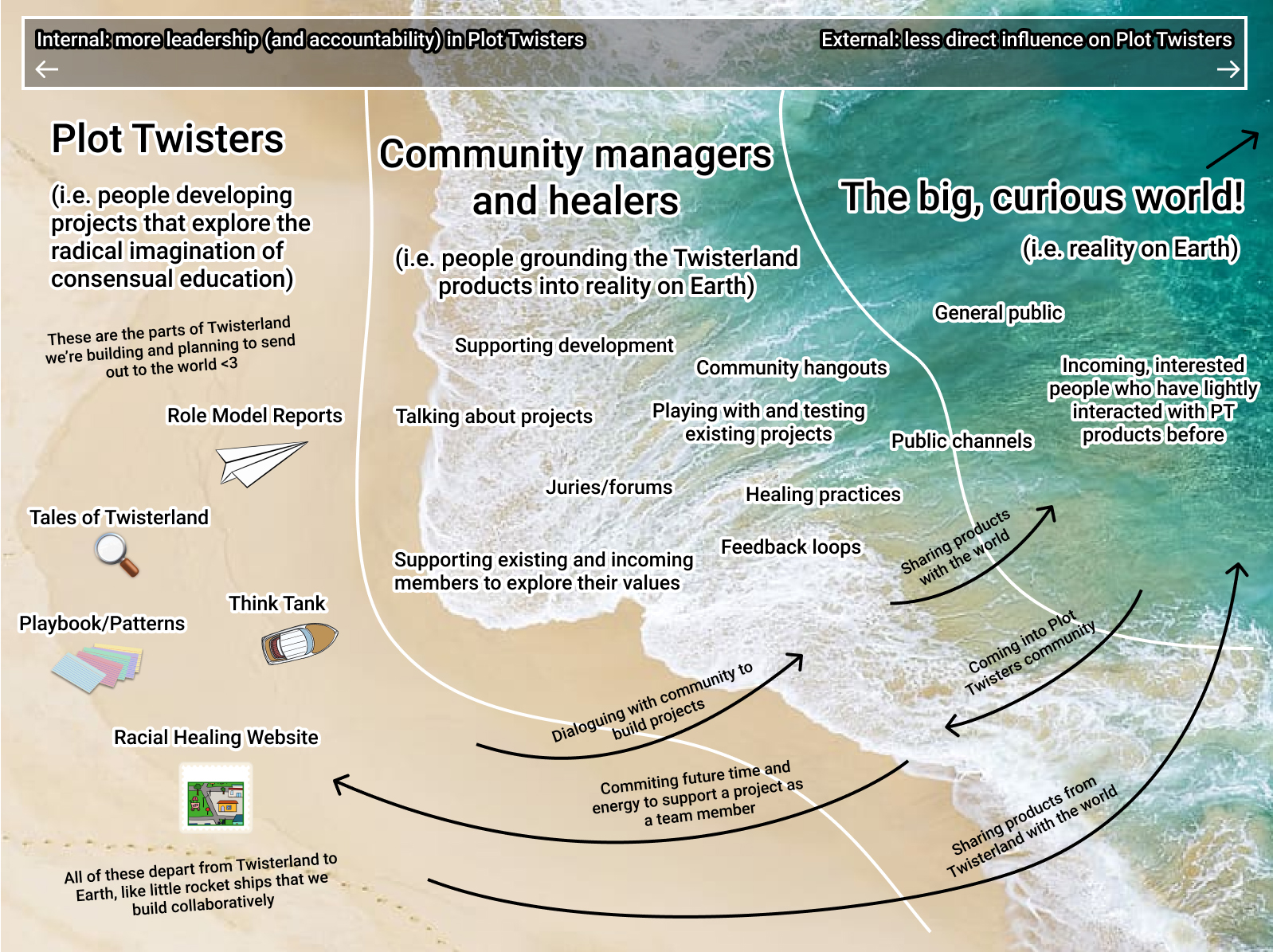

Jenny used a beach metaphor to describe our structure. The visualization shows our community as a gradient: on the left, people have more accountability over various Plot Twisters activities. As we move to the right, people have less direct influence on the Plot Twisters community.

Jenny used a beach metaphor to describe our structure. The visualization shows our community as a gradient: on the left, people have more accountability over various Plot Twisters activities. As we move to the right, people have less direct influence on the Plot Twisters community.Cat explains this beach metaphor in a blog post for the Excavations cohort:

Plot Twisters has always had an informal lean-in/lean-out standard for participation. No member is ever bound to projects, roles, or obligations for any length of time as long as they communicate with another team member. Broadly, there are no defined roles filled by defined people in Plot Twisters — our roles are more centered around where there is need and who has the strengths and capacity to fill them. So, there is no way to divide roles into buckets that make sense. There are currently members of Plot Twisters that joined for a project way back when, or joined to get involved in conversations that we were having at some point in the past, but aren't active presently. These people never filled in a specific role - they just contributed what they could, when they could, in a way that was empowering or interesting to them. We'd like to keep it that way. These people are the waves of the ocean.

On the other hand, even as Plot Twisters members lean in and out, start their own work, and roles in the community evolve—there will always be projects that Plot Twisters needs to maintain, improve, or continue: such as Role Model Reports, Tales of Twisterland, and our ever-growing Think Tank. There will always be needs associated with these internal projects — and fortunately, we have an amazing group of people who currently fulfill these needs. But, as our community expands, a big part of our governance model will be inviting others to lean in and out of these internal projects that our current team has fostered for so long. This is sand, internal projects that appear relatively the same for longer periods of time.

Meanwhile, the community was developing components of the Plot Twisters game world. The game’s imaginary universe, called “Twisterland,” will be designed to be played in solo mode or social mode and house journaling minigames, identity building activities, and conversation starters guided by non-playing characters. We began to recognize the link between our creative goal—to design a platform that embodied our values—and our pursuit of a transparent institution. Finally, we realized the elephant in the room: the audience includes us, we need this game for ourselves, and the best way to build Plot Twisters is to play it ourselves.

With its aim to normalize intrinsically motivated decision-making, emotional literacy, and consent, Plot Twisters’ Twisterland became an example of “dogfooding,” or the practice of using one’s own product in the process of creating that product. Jenny explained how she saw the beach metaphor connect to the larger world-building of the Plot Twisters game world:

In this beach visualization, the land is Twisterland. Twisterland is where the values of consensual education and work are the norm, and people are self-motivated to learn, create, and play. In Twisterland, people feel at home; there is a cultural sense of belonging, appreciation, and curiosity toward the planet and universe. Plot Twisters, a team of people who spend a lot of time in Twisterland, are bringing ideas from Twisterland to Earth, to make Earth feel a little more like home. Some of these projects include Role Model Reports and the Think Tank.

Co-design and circles

Moving forward, both Plot Twisters and our game world will explicitly adopt a governance structure based on two key methodologies: co-design (McKercher, 2020) and circles (Dana et al., 2021). Co-design provided specific guidelines for facilitating dialogue. Described by KA McKercher as the practice of “elevating the voices and contributions of people with lived experience,” co-design lists specific ways power may be imbalanced, from inherited privilege to extroversion, and how to build capability of all participants from different expertises and experiences. Circles structurally implements co-design by trusting groups in a community to make decisions together through consent, and convening group representatives to advocate for specific interests (Dana et al., 2021). Together, co-design and circles form the institution of Plot Twisters team and the groundwork for fostering freedom, play, mutual aid and decentralized storytelling (Winger-Bearskin, 2021) in the game world.

In the process of scrutinizing our governance structure and reflecting on our communication methods, we simultaneously developed a playful deck of cards to codify our language. Currently called the Plot Twisters Storytelling Cards, the deck contains 48 cards divided into four suits: Feelings, Needs, Strategies, and Structures. We anticipate the cards will be useful for cultivating “we-ness” (Steinberg, 2004) and proactive accountability (Kaba et al., 2020) prior to making serious commitments to shared projects, creative work, or resource exchange. The cards could also be employed in a restorative or transformative conflict resolution practice to recognize and repair harm; its vocabulary may empower people to communicate their feelings and strategies for healing, and their needs and structures for accountability (Schoenebeck & Blackwell, 2021). As a supplement to our community structure, these cards will be a go-to tool for fostering co-design and bridging across circles.

Onward!

Through practice-based research and a lot of self-reflection, Plot Twisters emerged from an era of unchecked hierarchy into a governance structure that formalizes the previously implicit shared values of freedom, play, and mutual aid. The Plot Twisters Storytelling Cards are one way to facilitate conversations about our lived experiences and the values we share, even though we come from different walks of life. Yet with the agency to play comes the negotiation of expectations: the protocols for creating relational contracts and mutual aid agreements in Plot Twisters are still in the making. Though we have codified our language, we now face the challenge of sustaining its practice. We believe that the decision-making process for consent and mutual care should be as open-ended as possible. However, establishing clear norms around one-to-one and group contract creation would ensure sustainable dialogue and accountability, similar to what KA McKercher proposes in co-design as a “duty of care” (McKercher, 2020).

We anticipate creating more tools and case studies to supplement these gaps in the coming months. One method we are interested in is augmenting card games with a dialogue documentation process, like a digital note-taking interface or a physical notepad, to collect important ideas that emerge in conversation. This process may parallel how stories in Indigenous story-spaces are woven together as wampum to protect and communicate a community’s shared values (Winger-Bearskin, 2021). A document could also serve as an ongoing record of roles, reminders, and boundaries.

This journey update celebrates nearly two years of learning firsthand, from first principles, how to run an organization that empowered wellbeing through communication. As our community continues go through changes as new and old members lean in and out of our communications, we look forward to seeing how our values and intended structures take shape. We will keep you updated on our twists and turns here.

References

Alberti, F. B. (2019). A biography of loneliness: The history of an emotion. Oxford University Press, USA.

Calvino, I. (1987). The Uses of Literature: Essays. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Damasio, A. (2005). The neurobiological grounding of human values. In Neurobiology of human values (pp. 47-56). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Dana, C., Hornbein D., Vincent, R., Schneider, N. (2021). Community Rules. Media Enterprise Design Lab.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Kaba, M., Rice, J. D., Sultan, R. (2020). Uncaging Humanity: Rethinking Accountability in the Age of Abolition. Bitch Media (December 8, 2020).

Schell, J. (2008). The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. CRC press.

Schoenebeck, S., & Blackwell, L. (2021). Reimagining Social Media Governance: Harm, Accountability, and Repair. Schoenebeck, Sarita and Blackwell, Lindsay. Reimagining Social Media Governance: Harm, Accountability, and Repair (July 29, 2021).

Schneider, N. (2021). Admins, mods, and benevolent dictators for life: The implicit feudalism of online communities. New Media & Society, 1461444820986553.

Spade, D. (2020). Solidarity not charity: Mutual aid for mobilization and survival. Social Text, 38(1), 131-151.

Steinberg, D. M. (2004). The Mutual-aid Approach to Working with Groups: Helping People Help One Another. Routledge.

McKercher, K. A. (2020). Beyond sticky notes. Doing co-design for Real: Mindsets, Methods, and Movements, 1st Edn. Sydney, NSW: Beyond Sticky Notes.

Walsh, M., Roberts, I., & Besser, M. (2013). Upright Citizens Brigade comedy improvisation manual. Comedy Council of Nicea LLC.

Winger-Bearskin, A. (2021). Decentralized Storytelling. Co-Creation Studio at the MIT Open Documentary Lab.